Mariasole Maglione (Gruppo Astrofili Vicentini)

Lorenzo Barbieri (CARMELO network and AAB: Associazione Astrofili Bolognesi)

Introduction

The CARMELO network not only records individual meteoric echoes but also calculates the hourly rate of meteoric activity. October is the month of the Orionids (ORI) shower. The October readings reveal a pattern consistent with the predictions of this shower, but they show an unusual activity that seems to trace that which occurred 31 years ago also by the Orionids.

In addition, this report comments on the observation of an unexpected outburst last September 4.

Methods

The CARMELO network consists of SDR radio receivers. In them, a microprocessor (Raspberry) performs three functions simultaneously:

- By driving a dongle, it tunes the frequency on which the transmitter transmits and tunes like a radio, samples the radio signal and through the FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) measures frequency and received power.

- By analyzing the received data for each packet, it detects meteoric echoes and discards false positives and interference.

- It compiles a file containing the event log and sends it to a server.

The data are all generated by the same standard, and are therefore homogeneous and comparable. A single receiver can be assembled with a few devices whose total current cost is about 210 euros.

To participate in the network read the instructions on this page.

October data

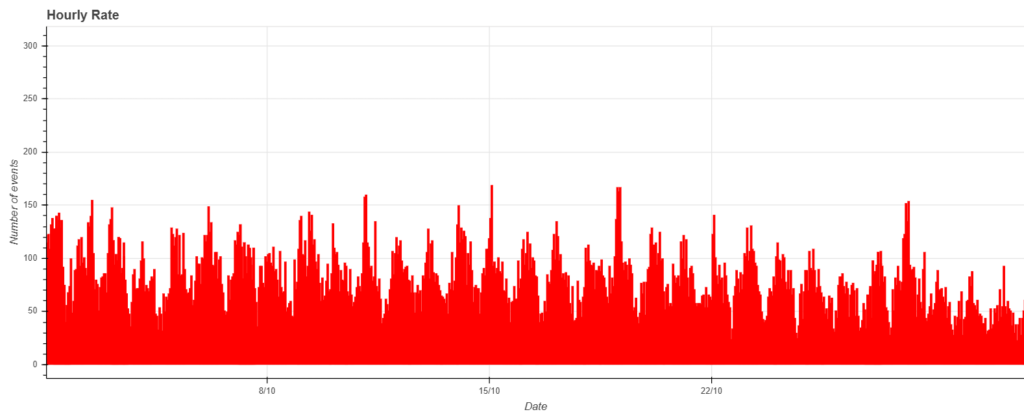

In the plots that follow, all available at this page, the abscissae represent time, which is expressed in UT (Universal Time), and the ordinates represent the hourly rate, calculated as the total number of events recorded by the network in an hour divided by the number of operating receivers.

In fig.1, the trend of signals detected by the receivers for the month of October.

Fig. 1: October data trend.

Orionids

The star of the month of October was the Orionids (ORI) shower, an annual meteor shower originating from Halley’s Comet (1P/Halley), one of the best-known and most studied comets in our Solar System. This shower is generally active between October 2 and November 7, with peak activity usually occurring in the days around October 21. During the peak, under ideal conditions, up to 20 meteors per hour can be observed. (1)(2)

The Orionids’ radiant is located in the Orion constellation, near the bright star Betelgeuse. This means that the meteors appear to originate from this area of the sky. For observers in the northern hemisphere, such as the CARMELO network, the radiant rises late in the evening and reaches maximum elevation in the hours just before sunrise.

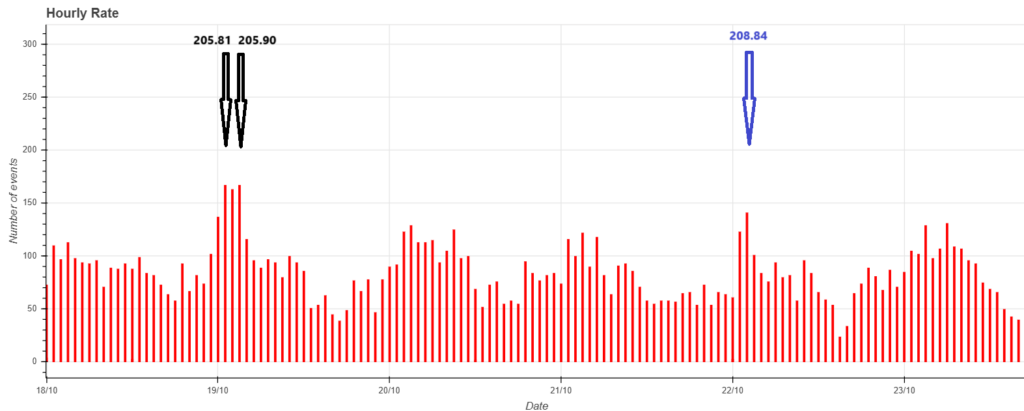

The hourly rate recorded by the CARMELO network shows an outburst on Oct. 19 between 1 and 3 UT, solar longitude between 205.81° and 205.90°, and then a second, smaller peak on Oct. 22 around 2 UT, solar longitude 208.84°, as we see in fig. 2.

This increase in activity on Oct. 19 is reminiscent of that recorded by visual observation by Koen Miscotte in 1993. He observed between twice and three times the normal activity at approximately solar latitude 204.5° (3). Should other observers also have come across the same observation, it would be interesting to investigate, 31 years later, the possible existence of a filament.

Fig.2: Peaks of the Orionids shower on Oct. 19 and 22, with respective solar longitude.

The peak of the epsilon Orionids (947 EPO), a shower derived from comet C/1914 J1 (Zlatinsky), was also expected on October 19. The temporal overlap of these showers could explain the observed increase in activity.

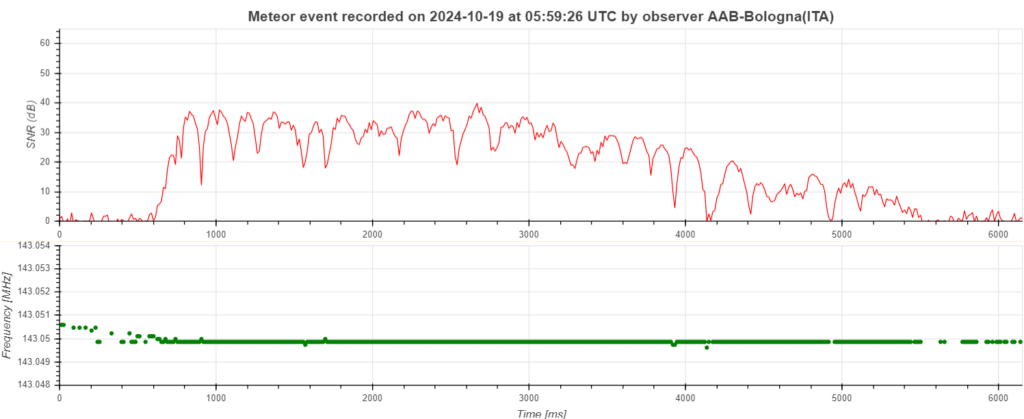

The Orionid shower is then particularly interesting because of the extreme speed of the meteors (about 66 km/s), which sometimes exceeds even the Perseids in terms of the rapidity of atmospheric impact. This high speed often produces bright meteors with persistent trails. An example is the one in fig. 3.

The plot shows a meteor recorded on October 19 at 05:59:26 UT by the receiver of the Associazione Astrofili Bolognesi in Bologna, characterized by a long duration. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) plot, at the top of fig. 3, peaks at 40 dB and remains high for more than 5 seconds, generated by a particularly saturated cylinder of plasma. In the early part of the plot, the meteor head echo is visible. In addition, fragmentation can also be seen, suggested by amplitude fluctuations due to the beat between contributions from paths of different lengths generated by a little “train” of fragments.

Fig. 3: Meteor event recorded on October 19 at 5:59 UT in Bologna.

The scattered nature of the Orionids shower can be traced to the numerous passes of Comet Halley, which over time has released large amounts of debris, which by crossing Earth’s orbit create a relatively large meteoric flux. As is well known, we will encounter it again in the spring when it generates the Eta Aquarids.

The September 4 outburst

On Sept. 4, 2024, an outburst with radiant in the Cassiopeia constellation, belonging to an unexpected and named September psi-Cassiopeiids (SPC) meteor shower, was detected by several radiometeor detection networks, as reported by P. Jenniskens and N. Moskovitz (4)(5) from America and T. Sekiguchi from Japan (6).

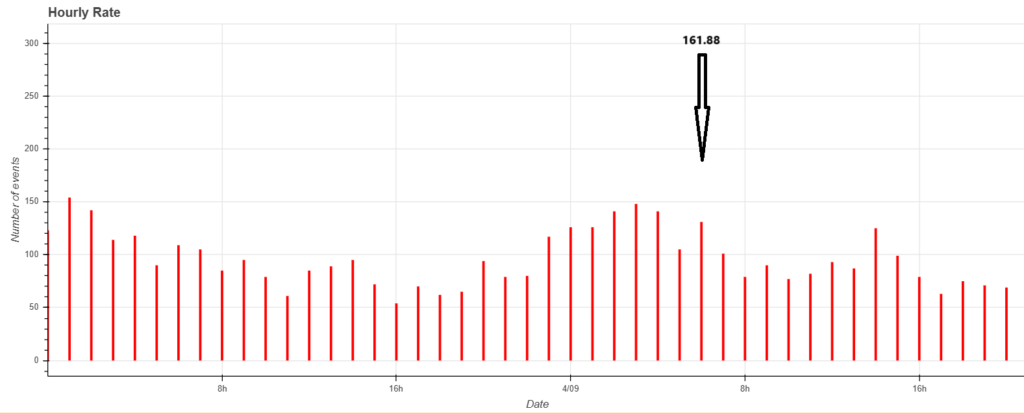

Jenniskens and Moskovitz write that the event had a short duration, with a period of activity between solar longitude 161.88° and 162.14° degrees. The meteors were detected at times between 6 a.m. and 1 p.m. UT.

The CARMELO network also seems to have detected this outburst. There is a spike in the number of events recorded at solar longitude 161.88°, at 6 UT, on September 4 (in fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Outburst detected on September 4 at solar longitude 161.88°.

The CARMELO network

The network currently consists of 14 receivers, 13 of which are operational, located in Italy, the UK, Croatia and the USA. The European receivers are tuned to the Graves radar station frequency in France, which is 143.050 MHz. Participating in the network are:

- Lorenzo Barbieri, Budrio (BO) ITA

- Associazione Astrofili Bolognesi, Bologna ITA

- Associazione Astrofili Bolognesi, Medelana (BO) ITA

- Paolo Fontana, Castenaso (BO) ITA

- Paolo Fontana, Belluno (BL) ITA

- Associazione Astrofili Pisani, Orciatico (PI) ITA

- Gruppo Astrofili Persicetani, San Giovanni in Persiceto (BO) ITA

- Roberto Nesci, Foligno (PG) ITA

- MarSEC, Marana di Crespadoro (VI) ITA

- Gruppo Astrofili Vicentini, Arcugnano (VI) ITA

- Associazione Ravennate Astrofili Theyta, Ravenna (RA) ITA

- Akademsko Astronomsko Društvo, Rijeka CRO

- Mike German a Hayfield, Derbyshire UK

- Mike Otte, Pearl City, Illinois USA

The authors’ hope is that the network can expand both quantitatively and geographically, thus allowing the production of better quality data.

References

(2) NASA CNEOS (Center for Near Earth Objects Studies)

(3) Peter Jenniskens (2006): “Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets”. Cambridge University Press

(4) Peter Jenniskens, Nick Moskovitz (2024): “Meteor shower outburst with radiant in Cassiopeia”. CBET 5442. Ed. D. W. E. Green, IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams

(5) Peter Jenniskens, Nick Moskovitz (2024): “2024 outburst of September psi-Cassiopeiids”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 9, 397-399

(6) Takashi Sekiguchi (2024): “2024 outburst of September psi-Cassiopeiids by SonotaCo Network in Japan”. eMetN Meteor Journal, 9, 400-402